The following is a conversation between Don Howard, President & CEO of the James Irvine Foundation, and Denver Frederick, Host of The Business of Giving on AM 970 The Answer in New York City.

Denver: I would suspect that most listeners have heard of Irvine, California down in Orange County around Los Angeles. It is named after James Irvine who also founded the James Irvine Foundation, one of the most important and highly respected foundations in all of California. It’s a pleasure to have with us tonight their president and CEO, Don Howard.

Good evening, Don, and welcome to The Business of Giving.

Don: I’m happy to be here.

Denver: Tell us who James Irvine was and some of the history of the foundation that bears his name.

Don: Mr. Irvine was an agricultural pioneer. He owned at the time about 20% of present-day Orange County. Turned that from grazing land into agriculturally productive land, innovated on irrigation and brought in some new crops and was a very successful man of the land in his time. Near to his death, he decided to put a little more than half of his holdings into a foundation to benefit the State of California. We’re still giving that money away today. It’s now valued at $2.5 billion, and we have the privilege of giving away about $100 million a year right now.

Denver: It started at about $5 million or something like that, so it has really, really grown.

Don: Well if I can tell you, if we held on to the land, we probably would be a much larger foundation as well.

Denver: You went from agriculture to real estate as California took off, but as you say, if you held it a little bit longer, who knows where it would be?

Don: One thing to know about the foundation is to think of it as: we’re an independent foundation. No family members involved at this point. No corporate interests involved at this point. Our governance is a board of 13 of us who represent the state in various and diverse ways. We have a focus on a single state, California, which granted at 40 million is a lot of folk, but on the other hand, it gives us at least a running shot at having a strategy.

So, Mr. Irvine, in addition to giving us these resources, gave us a focus on the state and a lot of latitude as to how we went about our grantmaking. We’re the only independent foundation in California with the state as a focus without having some overlay of health, in particular.

California is really two states. We have a state of quite a bit of affluence and folks who are successful in driving the economy, and then we have a part of our state– particularly inland portions of California– that is really being left behind.

Denver: Let’s talk about that state for a moment. The economy of California has been on a tear. It is now the fifth largest economy in the world, and it was only five years or so ago that it was as low as 10th. Yet, one in five Californians live in poverty, which is significantly higher than the one in seven average for the rest of the country, and it has the highest child poverty in the nation at 22.8%. Why is that the case?

Don: California is really two states. We have a state with quite a bit of affluence and folks who are successful in driving the economy, and then we have a part of our state– particularly inland portions of California– that is really being left behind. It’s not lost on me… I live in San Francisco… that I can drive two, three hours from my home to Fresno, and one place…the average home price is approaching a million dollars; in the other, you have homes that are in the $ 200,000 and $300,000 range. The disparities are acute, and they’re present, and they’re very much in our face.

Forty per cent of the state cycles in and out of poverty over time.

Denver: Many experts agree that what happens in California often foreshadows what’s going to happen for the rest of the country in the years ahead, and I know when you started your tenure here, Don, you traveled around the state listening to people and their concerns, one community after another, and I assume you’re still listening. What did you hear? What did you learn?

Don: Quickly, your question about what’s going on in California. Important to know that in addition to being the highest poverty state in the union, we have the two poorest congressional districts in the United States; Fresno, in particular, is the poorest. This is one example of the kind of communities that are under-resourced and are being left out of the economic explosion. And the listening tour that you mentioned, I spent time early on in my role as CEO traveling around the state talking to leaders in different communities up and down from different sectors, asking them what they thought we should focus on at Irvine in the next generation.

And they pointed to a couple of important issues. The first thing is economic disparity. The haves and the have nots… how that goes against our values as a state, our values as a country, and importantly, what that leads to in terms of an unsustainable economy. It’s just not a sustainable situation to have: 4 in 10 Californians who are living in or on the brink of poverty. Those are the estimates we use. Forty percent of the state cycles in and out of poverty over time, and that’s not a sustainable situation.

The other thing I heard which we’ve also taken up as a goal is that folks are being left behind politically. That the power imbalance in our state represents what’s going on in the rest of the country, and those folks who are working two and three jobs were being paid minimum wage and struggling to get ahead, who can’t get on a pathway to the middle class, they’re feeling disconnected and disaffected. They are not voting, and they are not involved, and it shows. We have leadership, political leadership, in particular, in communities around the state, that just does not represent the people of California.

Denver: And they feel trapped, don’t they?

Don: They do. Many folks reported this. We did another series of listening events where we talked to low-wage workers across the state, and 500 or so in multiple languages in the course of 10 or 11 different sites. What we heard time and again from them was a sense of being trapped. Being on a hamster wheel. Not being able to get ahead. A sense of not being connected to their community and not having the time to connect to their community, sort of being on their own, and just a tremendous amount of anxiety. You think about the worry budget of a low-wage person, and you think about the economic insecurity, and you think of many of our low-wage Californians, our immigrants–often new immigrants– and there’s insecurity in their status and in their families.

Then there’s an overlay of often young families with kids, and the insecurity over the future for their children. In those listening sessions, we asked folks in various ways to depict their aspirations for their lives, and time and again, it was just so consistent. We have folks draw pictures. We had folks use words. We had folks tell stories. Folks want what all of us want for our families. We want a house. We want physical security, food security, economic security. We want a chance for our children to do better than we did. Often for folks that means college.

I sat in one session with Chinese immigrants in San Francisco, often working in the hotel and restaurant trade. Even though they weren’t speaking in English to me, they were drawing pictures, and they were drawing pictures of picket fences, homes, kids in college holding degrees. The aspiration to get into the middle class is as strong or stronger now than it’s ever been. Unfortunately, we all know from the data, odds are no longer in your favor that your kids will do better than you. That’s what we’ve taken up as our goal.

Don Howard and Denver Frederick inside the studio

Denver: Let’s talk about a couple of things you’ve done in that regard. In California, like the rest of the country, there is this huge middle skills job gap. Well-paying jobs that sit there because employers just can’t find qualified candidates, and in California, that number is staggering. It’s 1.4 million jobs. So, you are now looking to make an impact there. What specifically are you doing?

Don: We’ve said that’s one of our overarching goals. We have two of them. One of them is enabling folks to have greater economic opportunity and get in and stay in the middle class. What we’ve been doing there is looking at evidence-based efforts, evidence-based programs that can bring folks’ skills up and have them be prepared and placed into these middle-skill jobs. So, we’re looking at programs that deliver more than a high school degree, typically less than a baccalaureate degree, and are training folks for professions that have family-sustaining wages and a pathway to a real career.

Think of organizations like Year Up, working with disconnected youth, or the Center for Employment Opportunities, working with folks coming out of the justice system. Those organizations have evidence that they can make a difference. What we’ve done is we’ve asked them to tell us: what do you need to scale up your impact? Tell us how much more you could do… and what it would cost.

And we’ve been making flexible, general operating support investments over longer periods of time to help them achieve their goals on their terms. That’s been an important part. That’s called our Better Careers Initiative, and that’s been one of our new flagship initiatives we’ve launched. Our board committed $120 million over six years in order to help that group of organizations step up their game and hopefully, in the process of doing that, we’re going to take our cue from them on how we can invest in things like research, strategic communications, evaluation, maybe policy change, built on what they know from their perch as leaders in the community to help drive systems change that goes beyond the direct impact of their work.

Denver: Let me pick up on something you just said there, and that’s strategic communications. Do employers communicate clearly the kind of skills they need? Or is that a gap that exists?

Don: I’ve just recently spent time making the rounds talking to the largest employers of middle-skilled staffers across the state. Think PG&E, Chevron, Salesforce, UPS, AT&T, and Kaiser is another example. I’ve been so impressed by the recognition they have that we share that the current situation is not sustainable. They have great needs for hiring. They can’t meet those needs with the traditional education systems, and they are no longer and never were built up to provide that kind of training internally.

So, what I hear from them is they have really a moving target with jobs. Take Kaiser as an example. One thing I was really impressed, they are conceptualizing a new job that is a paraprofessional, focused on mental health. They are overrun in terms of the need to supply mental health services. They know that’s important for health prevention and health advancement for their members, and they can’t find enough MSWs and MFTs to do the mental health work. Not everyone’s going to get a 50-minute appointment with a skilled professional. So, they’re conceptualizing a new role and are thinking about how they can partner with nonprofits and community colleges to design that role, to credential that role, to recruit those folks, and to get them on boarded.

Denver: That’s great.

Another huge cohort in the state are the 5 million Californians making less than $14 an hour, and many of them are making less than $10 an hour. Now, your efforts here are around something you call a Fair Work initiative. What are the issues? And what is your strategy?

Don: In addition to not having jobs that pay sufficient wages, there are a considerable number of folks who have jobs, low-paying jobs, but are often not getting to take home the wages they’ve earned. We believe every Californian should take home the wages they’ve earned. Unfortunately, there’s about 600,000 Californians who are losing we estimate an average of $3,400 each to wage theft every year. So, the total wage theft in the state is estimated at $2 billion. It falls just proportionately on the 600,000 minimum wage workers, and the average per worker is $3,400. Not only are you working a job that pays– the average wage here is $12.50 an hour– you might be working multiple jobs, and you’re losing through wage theft $3,400 a year.

Denver: Give us an example of wage theft.

Don: Wage theft… take for example a restaurant worker who might be encouraged to work through their break time, or who might not be paid for their break time, or who might not receive their lunch hour, or who might work more than 40 hours but not receive overtime. If you take an agricultural worker in the fields who might be transported from one work site to the next, but not paid for the time they’re in transportation. Often, this sort of wage theft is happening in sadly small/ medium-sized businesses, who are keeping themselves afloat by in essence subsidizing their economics by not paying their workers what they’re due.

Oftentimes, that’s immigrant wage theft which adds another complication culturally and linguistically. Many of the folks who are losing their wages are not likely to want to go into a public office and complain, so they suffer in the shadows. What we call our Fair Work initiative, thanks for asking, is an $80 million initiative over six years. Similar construct. We look at the organizations that best address wage theft. They are worker centers. These are centers like the National Day Laborers Association or Restaurant Opportunity Centers, National Domestic Workers Partnership where folks are connected as workers to other workers in a culturally competent setting and can bring their wage complaints into that CBO or that nonprofit, and that nonprofit can partner with our tremendously talented labor commissioner, Julie Su in California. They have a strategic partnership with these worker centers to bring wage cases forward and to bring them in a way that can strategically affect the industries in which they’re brought.

One great example of this is a case brought by the Chinese Progressive Association, a San Francisco based work center against the dim sum chain, quite well-known, called Yank Sing, and they brought a wage theft case into court with the labor commissioner and recouped $5 million in lost wages. So, our goal for our Fair Work initiative is returning $250 million a year of lost wages by scaling up and strengthening the worker centers and helping invest in that partnership they have with the labor commissioner.

There’s such a thing as a free economy, even an economy with policies that guide the economy; those policies can either favor or not favor low-wage workers. And we believe that more workers with civic engagement and political power will change the rules of the road and create better conditions for themselves and their families.

Denver: Fantastic. Irvine, like some other foundations such as Ford, is focused on inequality. You alluded to it a moment ago, you see a very clear connection between economic inequality and political inequality. Speak to that. And how has that informed your approach?

Don: We’ve come to appreciate that these are really two sides of the same coin. If you are a low-wage worker struggling with multiple jobs, maybe your immigration status is being challenged or is uncertain, and you’re raising children; your ability to get involved civically is pretty much zero. And you might feel disaffected and disconnected and not have any motivation to be involved otherwise.

Conversely, our economy, as much as folks might want us to believe, there’s such a thing as a free economy, even an economy with policies that guide the economy, those policies can either favor or not favor low-wage workers. And we believe that more workers with civic engagement and political power will change the rules of the road and create better conditions for themselves and their families. And there’s a small part of worker democracy… if I take that Yank Sing as an example we talked about. Those workers coming forward and organizing themselves with the Chinese Progressive Association to bring this action was a very political action. Workplace democracy or workplace engagement is an onramp to civic engagement and political involvement in our communities.

To be able to invest in organizations that are helping to right that wrong is a powerful motivator.

We provided a ton of flexible support knowing that this is not a time to be prescriptive. This is a time to lean in, make those investments. Our board didn’t bat an eye. In fact, they were well ahead of us. It felt to us, I know also to them, that we were protecting California values, protecting our economy, protecting our community’s safety, and that this was the right thing to do, regardless of partisan affiliation, regardless of how you figure out the politics of it all.

Denver: Bringing in this political element as you have, is something that many foundations shy away from. As you know, they like to play it safe. Don’t want to rock the boat. Avoid controversy if they can help it. Do you see that starting to change in the foundation community?

Don: I do. As I said before, our board is really representative of folks from across the state. We strive to be pragmatic, solutions-oriented, and frankly, I would say, cross-partisan or centrist. And it’s been really interesting for me as the leader of the institution to watch our board’s thinking on this evolve over time. As they become aware of things like the wage theft that’s happening in our state, they’re appalled. They don’t think of that as a partisan issue or a political issue. They think of that as fairness. And it’s just wrong.

So to be able to invest in organizations that are helping to right that wrong is a powerful motivator. I take another thread of our work and lift it up– which is work we’re doing around protecting immigrant rights. We’ve got a longstanding investment in helping communities integrate newcomers into the systems of their community. As immigration status became more challenged, and as we’re seeing the kind of fearfulness and divisiveness around immigrants and immigration, we’ve pivoted and invested now last year, I think, $ 10 million to protect immigrant rights. Know your rights kind of sessions, equipping folks with education to be able to protect them and their families, as well as to help beef up the policy advocates who are working in communities across the state on immigrant rights.

We provided a ton of flexible support knowing that this is not a time to be prescriptive. This is a time to lean in, make those investments. Our board didn’t bat an eye. In fact, they were well ahead of us. It felt to us, I know also to them, that we were protecting California values, protecting our economy, protecting our community’s safety, and that this was the right thing to do, regardless of partisan affiliation, regardless of how you figure out the politics of it all.

One of our mantras is: We’re out of the answer business. The answers are in the community. Our job is to go find them and give them money.

Denver: Another way you pivoted, Don, is with the grant making at the foundation, which has gone from a program model to an initiatives model. Explain what each is and the benefits you saw in making that change.

Don: Part of my mandate coming in with the board was to up our game, to think about how we could, by taking more risk and being more nimble, have greater impact with the resources we have– both our time and our grant making. Having spent a decade or so at the Bridgespan Group working for a number of foundations, I have a strong point of view that an important way to do that was to eliminate program silos and try to create a single institution pursuing common goals.

One of the first things we did was…our mission has long been expanding opportunity for the people of California. We started to get specific. Economic opportunity and political opportunity and recognizing that as a big state, we decided to focus on workers in California who are working and struggling with poverty, focusing on California’s workers who are struggling with poverty as a way to anchor our investments in economic opportunity and political opportunity. Then what we decided was rather than having programmatic silos that had some sort of eternity to them… some unending dimension to them… we wanted to have initiatives with clear outcomes, set timeframes, and a dedicated source of resources that we could advance those broader goals.

And in doing that, we shifted away from having individual teams based on programs, and now we have… each of these initiatives has a team, cross-functional and focus on that team… typically have half of their time dedicated to that. So they are on at least two teams, or actually, one of our goals as we sunset and culminate some our previous work… is to get down to having folks on no more than two teams. It’s easy to split people too much. Our goal is to have folks who aren’t wedded to a single initiative. There’s a whole set of reasons to do that. This notion of having some unanimity around what we’re trying to accomplish, trying to disconnect an individual’s loyalty to the institution from a loyalty to the program.So that we can be clear-eyed about whether something’s having results or not, and we can be nimble and adapt as things go.

Another is to move from having content experts who are hired to design a strategy for a program to folks who are more generalists, have a lot of intellectual curiosity and can be good at strategy development and business development, which we think is core to developing good initiatives; able to work with grantees and collaborate. Another part of it is getting out of having a programmatic theory of change. One of our mantras is: We’re out of the answer business. The answers are in the community. Our job is to go find them and give them money. So, we’re trying to recognize that leaders in the community have the best answers. We’re not going to conceive…

We try to configure each initiative to have a core set of grantees that are best in class, if you will… then as a cohort, get their advice and direction on: how we do other investments, and hopefully build the strength of that cohort so that as our funding sunsets over time, they’re a stronger, more sustainable field.

Denver: People closest to the problem are closest to the solution.

Don: We try to configure each initiative to have a core set of grantees that are best in class, if you will, including some earlier stage, high potential grantees, but particularly those that represent parts of the state that have less capacity or communities that aren’t addressed by the larger nonprofits. Create that cohort, invest in each of them in the cohort’s scaling, and then as a cohort, get their advice and direction on: how we do other investments, and hopefully build the strength of that cohort so that as our funding sunsets over time, they’re a stronger, more sustainable field.

Money doesn’t flow to the best ideas per se. You have to make it happen.

Denver: Very sound approach.

You just said that you were at the Bridgespan Group, at one of the preeminent consulting groups in the sector; you were there for almost a dozen years. As a matter of fact, the Irvine Foundation was one of your clients. Is there any skill sets or experiences that you gained in your role at Bridgespan that has really served you particularly well as you lead Irvine?

Don: Absolutely. First, it’s probably also worth noting that I was a business consultant before being a nonprofit consultant. We had a joke that Bridgespan, particularly in the early days, it was sort of a place for refugees of management consulting firms, and I fit the bill. My transition into the social sector was through activism around HIV in the ‘90s, and I just couldn’t go to work every day and work in things that didn’t seem to matter, and I was looking for some way to transition myself into the social sector, and there was Bridgespan.

Denver: It’s a halfway house for you.

Don: It was exactly half. Funny you say that. When folks ask what was translatable from a business consulting background. Well I’d say, it’s about half. Some of the underlying concepts, the analytic approach, organization culture; a number of things just translate very well. Others entirely had to be remade. The notion of setting impact goals, how to think about making tradeoffs in a world with metrics; either too few metrics, or metrics that aren’t necessarily apples to apples. Trying to think about imperfect capital markets. Money doesn’t flow to the best ideas per se. You have to make it happen. As my colleague, Tom Tierney of Bridgespan says, particularly in philanthropy, excellence is self-imposed.

So, there’s just a different set of dynamics. The one thing that I would say has been most important in my role at Irvine is the ability to work with very diverse groups of people to come to a decision. And I hadn’t appreciated just how much training I got as a consultant in bringing folks along, clarity of the challenge, using data and analytics to inform, and also bringing the group as an organism together to become more united around a common purpose. I find I do this time and time and time again within our work at Irvine and as a leader outside of Irvine.

We are not social change architects as we much as we might think we are and be asked to be that. We often get asked questions that are crazy. We’re not the experts. The experts are in the field and returning the rightful ownership of ideas to leaders in the social sector and to their communities and the beneficiaries they serve.

Denver: That’s particularly important in the social sector. You do it there more than just about anywhere else.

There are so many issues that face foundations today– the power imbalance between the funder and the grantee, and this call for greater transparency and so many others. Is there a particular one that you really have your mind wrapped around these days?

Don: It’s important to remind ourselves the core business process of a foundation is allocating resources. Resources in the public benefit that are intended for the public good. So what I think about are some of what I’ve experienced as a consultant and as a leader in a foundation, the barriers to doing that well. So, what we’ve been working hard at is creating an architecture that allows us to make tradeoffs…so, we see initiatives relative to another initiative, how much can we advance common goals, how much do they deploy our approach, do we find we get stronger, better at an institutional approach to our work, how do we build the roles and relationships in the institution to create the right propositions for us to make tradeoffs around. Really have been focused on trying to undo the pathologies of philanthropy that lead to bad decision making, about how to allocate resources. So, that’s been high on my mind.

I’d say the second thing has been really returning the leadership, particularly around strategy and innovation, to the field. We are not social change architects as we much as we might think we are and be asked to be that. We often get asked questions that are crazy. We’re not the experts. The experts are in the field and returning the rightful ownership of ideas to leaders in the social sector and to their communities and the beneficiaries they serve.

I’ve pushed decision making down from a single person or a small set of folks to an executive team and a program management team.

..no more charades about getting everyone’s input and then doing whatever’s already preordained.

Denver: Tell us about your corporate culture. Goodness knows Bridgespan had a great one. But what are you specifically doing to shape it? And what do you think makes it a special place to work?

Don: We’ve made this significant organizational transition over pretty much a 3-year window. Three program areas, we sunsetted all of that. It turned out that there were like 10 different strands of work across the three. In doing that, we’ve changed roles; we’ve had about a little more than half of the staff are new over the last three years, and we have a new process of doing our work and a new strategy. So much change has occurred.

We made one of our top two priorities of the year to be strengthening our culture, binding folks together, creating common sense of purpose, and identifying a new set of values that would imbue the work that we want to do going forward. And we are in the thick of it. One of the things I did recently was to have lunch with every staff member to just hear directly what we could be doing to strengthen our culture. We’ve done any number of other approaches to gathering data, and now we put ourselves on a hook, particularly as a leadership team, to address some of the weaknesses in our culture. So, we’re very on it. One right now that we’re working hard at is getting clear about decision making rights. Now that we have a metrics model, who gets to make which decisions? I’ve pushed decision making down from a single person or a small set of folks to an executive team and a program management team. We’re trying to… decisions under $ 1 million for resource allocation get to be made by our program management team. Those are the lead program folks. So in trying to distribute leadership and decision making more, it’s become more complicated.

If I told you the questions I used to get, you’d be amazed. Now, getting more clarity about who gets to make decisions… and also being also honest and clear with folks; where input is possible, where it’s not, and if we gather input, we have to use it. So, no more charades about getting everyone’s input and then doing whatever’s already preordained. I think the question was: what should the holiday schedule be next year?

Decision making is core…. better internal communications because we have fewer natural homerooms with people on metrics teams, and we’ve completely revamped our talent advancement system which may be a podcast for another day. But we’ve moved to a model that’s much more equitable where we have competencies for roles at different levels. Everyone with the same competence gets paid the same amount. No more negotiating prowess. No more who you knew. No more when you came in. It’s based on clear competencies, and we’re trying to develop folks to grow in those competencies. That clarity is actually unnerving. What we’re trying to do now is spend more time being clear about what it means to have that kind of a compensation system and that kind of a professional development system, particularly the role our advisors play as coaches to each of our staff members.

Denver: Change like that? You’re always going to break a few eggs in the process, but you’ve got to do it. Just comes with the territory.

Don: We’re super committed to equity internally, and it really is the focus of our strategy for impact as well. I think compensation systems are the place inequity can really unfortunately manifest themselves quite quickly.

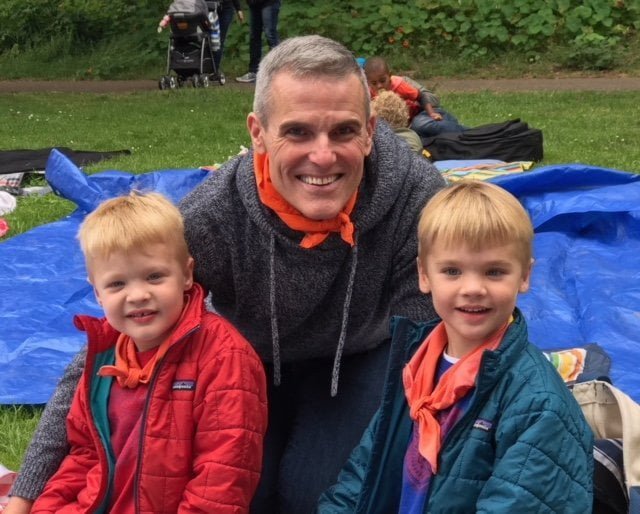

Don and his two sons, Grayson and Boone.

Denver: That’s why I’m so impressed by what Salesforce has done and what Marc Benioff has done. It’s really just a great model for everyone.

Let me close with this, Don. You’re a fairly recent parent… of twin boys, no less. Anyone who is a parent knows how a child can change their perspective on so many things. How has yours changed as it relates to your work and leading the James Irvine Foundation?

Don: I would not have planned this. When my predecessor, very wonderful esteemed leader, Jim Canales, told me he was going to transition out of the foundation, my boys were just about a year old. I initially passed and said: this isn’t my chance to take on the CEO role. I’ve got newborn kids.

The things I’ve learned? A couple of things; first, I should do a shout out to my boys, Boone and Grayson. Second, to say, they made me a better leader. When I am with my boys, I am all in with them, and I have to be very present, have to be very in their minds which is a very “ in the moment” time. I spend time playing with them on the floor where it’s that issue, it’s that disagreement, it’s this particular need they have, and it gets me out of the cycling and overthinking of work. I’ve become a more intuitive leader as a result of having time where I just am not going to think about work. I don’t want to lose that time with my kids, and twins don’t allow you time to multitask. My phone is not out when I’m with the kids.

Second thing that I’ve come to appreciate is: we are at risk of handing to our children a democracy and an economy which only works for a few. It scares me. If you layer on climate change and other big threats, I find myself much more – I have a greater sense of urgency and a sense of accountability to my own kids to make sure that when they’re getting ready to take the lead on something, we hand them something that they can still work with.

Denver: You’ve got more skin in the game. No doubt about it.

Don Howard, the president and CEO of the James Irvine Foundation. I want to thank you so much for being here this evening. What’s on your website that you think listeners might find to be of particular interest?

Don: Two things I’d recommend you look at. We have a link to the results of our community listening sessions, which I think is a really rich trove of information from all of the listening sessions we did around the state. The second thing I’d look at is the list of our core grantees for our two new initiatives; Better Careers Initiative and our Fair Work Initiative. They are heroes doing amazing work in our community, and the more folks who know more about what they’re doing, the better.

Denver: Thanks Don. It was a real pleasure to have you on the show.

Howard: Likewise. Thanks for having me.

Denver: I’ll be back with more of The Business of Giving right after this.

Don Howard and Denver Frederick

The Business of Giving can be heard every Sunday evening between 6:00 p.m. and 7:00 p.m. Eastern on AM 970 The Answer in New York and on iHeartRadio. You can follow us @bizofgive on Twitter, @bizofgive on Instagram and at http://www.facebook.com/BusinessOfGiving